Have You Eaten Yet?

My grandmother Christine grew up during the Great Depression in the United States and used to tell us stories about waiting in line for bread and broken macaroni, and like most people who lived through that time and other such collective traumas, I don't think it ever left her. But I can’t say that it scarred her, mostly because it was impossible to get a word in between plates of whatever magnificent thing she was cooking that day. Because, you see, happiness, security and love itself were lived in the acts of eating and more specifically, of her feeding anyone who came through her door. I can still remember walking into their house: everyone entered through the back door, which led to the kitchen. She was always on the phone and the cord would form a limbo wire under which we had to snake in order to enter. In between talking, smoking a cigarette and stirring that ubiquitous pot of sauce that was on the stove she would stop and hug us individually. By the time we were all teenagers we were all at least a few inches taller than her, especially Vin: whenever he wrapped his arms around her she would vanish momentarily. But after she finished cackling she always asked the same thing. “Have you eaten yet?”

Most of Italy still honors the Sunday lunch tradition, more of a ritual depending on where you go and how long you stay. It really starts at lunch and lasts for most of the day and is the sort of thing that defines the Italian family to most of us, both those who lived it and those who have seen it captured on film. It was not every Sunday in my family but it was many, and it did last for all those many hours. It always started with antipasti from the local deli spread on flat, hard plastic platters with removable dishes built for purpose, the likes of which I have never seen since. It was always cheese, salumi and olives, and there were always debates about who made the better sopressata and why. Then it was pasta, a gut busting combination of meatballs, spaghetti, and miles of bread. After an important and necessary pause there was a meat dish that would have seemed to any rational person to be overkill but was to us, quite a normal thing. She was a dab hand at roast beef and did something to broccoli that I have never been able to replicate but think of more often than I can say. Once we cleared the plates there was an intermezzo of fennel, then fruit and nuts, and finally a spread of pastries that spanned the width of the table. Someone had often baked and when it was Aunt Chris, we knew it would be the unparalleled rum cake, always decidedly heavy on the rum.

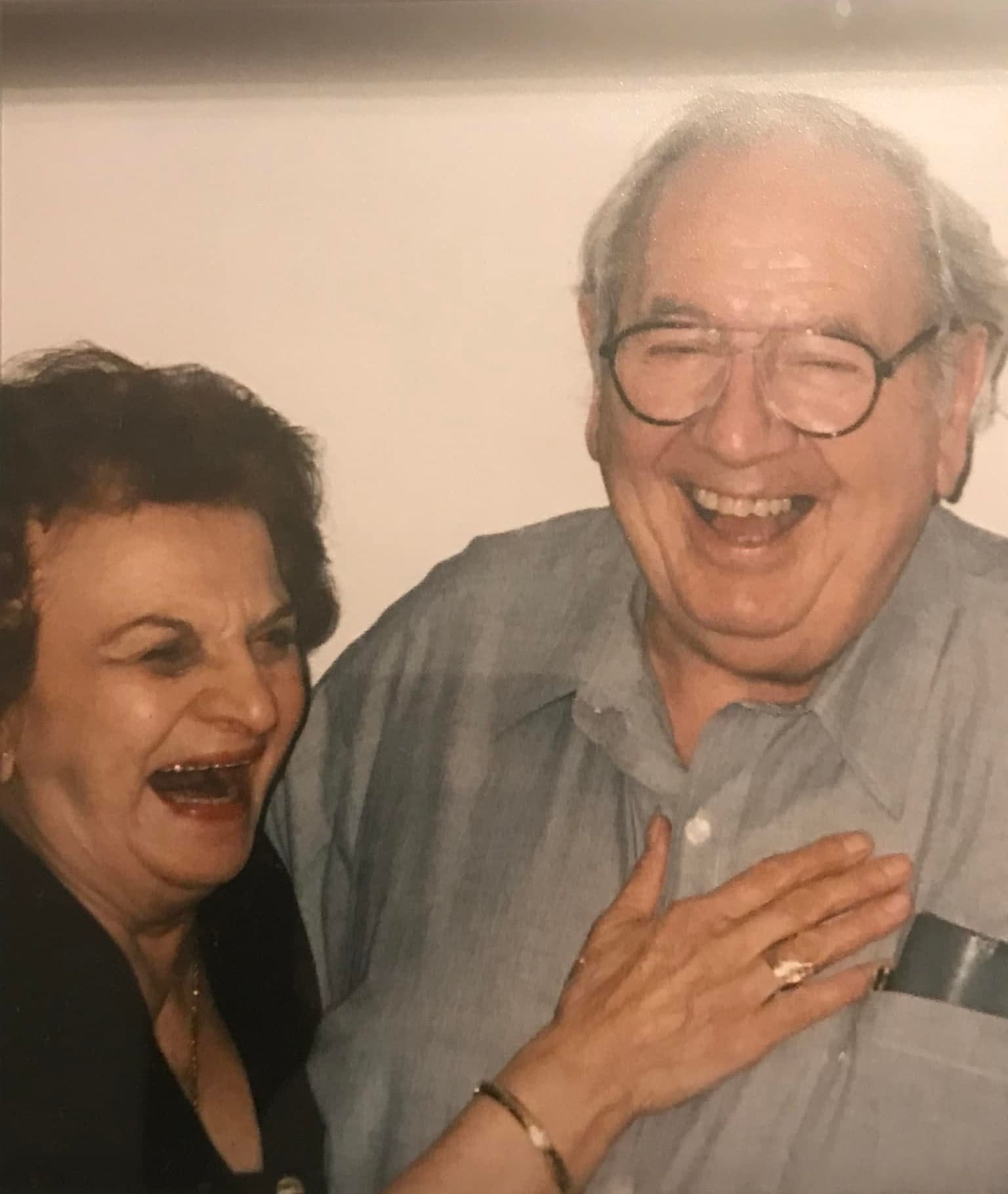

My grandmother hardly sat for any of it, and when she did she took the chair closest to the kitchen so that she could dip in and out as she needed. Truth be told, I have very few memories of her eating. She never let anyone wait for her to start and I think that sometimes people forgot she wasn't there, because she was so palpable in every dish on that massive table. She could keep the conversation going even when she was out of the room and never missed a beat, even if she was back at the stove stirring sauce. And then she would appear, usually towards the end of the meal, as if she’d been there the whole time. There was no applause for her and no furtive wiping on an imaginary apron in the hopes of earnest accolades. On bigger holidays like Christmas Eve, she would stand behind my grandfather's chair and put her hand on his back and ask him how everything was while he kept his eyes on the prize and continued to clean his plate. His muffled approval through mouthfuls was all she needed, and she would look at each of us with her piercing blue eyes and smile wide enough to draw the point of her nose over her top lip.

She always zeroed in on the one friend who’d come for the first time, the new boyfriend or girlfriend who’d been brave enough to ask for a seat. She’d cast that gaze on them and ask if they ate like this at home; if they answered with a look that suggested they were about to burst, she cackled in delight. They were always invited back. Everyone was.

It was clear towards the end that things were not right with her on Christmas Eve, that final year. It had always been her finest hour but this time she couldn't seem to keep up with all of the dishes. Everything was a bit less spicy than it usually was, and there was a sense of labour in them that had never appeared before. It was clear that she had struggled to finish, and that she had been forced to cut corners by virtue of her failing strength. She leaned too heavily on my grandfather's shoulder at the end of the meal and when she asked how everything was, he held her hand in his and told her it was good, although truth be told, he didn’t have much of an appetite. He knew that she was going to be leaving soon and made sure that we all ate together, that one last time. He kept her secrets and shared her burden until the end.

I remember the last time I talked to my grandmother in 2004, in the earliest days of spring. I was in school, I had a boyfriend, I had a job that I liked. I was going to be studying in Central America later that year; there seemed to be a direction that I was moving in, and that direction was a fine one. She was proud of me, and we spoke like adults, like friends. I imagine that I must have been the person on the other end of the phone cord that stretched around the kitchen and that maybe someone else would have had to limbo underneath to pass through. We hung up the phone and I told her how much I loved her, because I had begun to see how important it was to say that, to anyone and any time it was true. She told me she loved me too, and I heard her raspy cough on the other end and knew she needed to sit down a while. I hope she ate something after that.

Her death was too sudden for any of us to understand or make sense of, and I think that we all still ache about it in our own corners and in our own ways, even though it’s been more than twenty years. And she wasn't perfect, by any means. She didn’t suffer fools but her definition of them could sometimes be too wide, and too many people didn’t make the cut. She was unforgiving and made no effort to hide it, and the potency of her presence made it difficult to live in that shadow. Conversely, she could be stubbornly loyal to those who didn’t deserve her protection, and it forced her to make hard choices. She had her reasons, and they stayed hers. And I know that she held onto the deepest secrets that all families own but in ours should have come to light, because she could not bear the thought of losing the beautiful Sunday lunch table, where everyone was welcome and if she just cooked enough, it would all work out.

Because those that Christine loved far outweighed those that she scorned, and the fire that burned in her was implacable. She was brave, and fierce. She watched me suffer through a particularly difficult adolescence brought on by too much, too fast. She saw me in hospitals and clinics, and she witnessed my pain. She was unflinching, and sat by me in times when no one else had the stomach. I think she suffered as much as I did sometimes, wracked by the helplessness of how to fix something that isn’t broken and punctuated by the madness of it all. She was also brutally honest, the only one who could be so brutally honest. That ferocity, that unbelievable ferocity, I have never known it since.

It has taken me a long time to understand that people can be tough without being hard, and when I look back on my grandmother I see the difference in a way I’d missed, too often. I see her so often in my mind, a spindly finger pointed in someone’s direction that could exalt or condemn them while those magnetic blue eyes danced and laughed. I speak to her through those thoughts, through the little moments like these when I look back into the far, precious corners of my mind. If I were lucky enough to choose, my final meal would be her fluffy meatballs in sauce, a taste that only increases in flavour as it becomes a more distant memory. Yes, I idealize Christine DiGaetano, and so what if I do. You all have your heroes, leave me to mine.

Besides, I know that she would have loved you all. She would have teased you relentlessly and I bet you would have loved it. She would have laughed with you and given you that look she had, the one that I feel in myself sometimes which is the very faintest veil of irony over the deepest feelings of love. She would have told you about how my grandfather was crazy but she married him anyway, and she would have passed that same look onto him as my grandfather sat over the day's racing forms or lottery tickets. She would have forced you to sit at the table but you wouldn’t have wanted to leave her side in that comically small kitchen, because just being near her felt good and warm and safe and you’d know somehow that you’d never find that again, not like that. I don't remember how many times or even if ever I heard my grandmother tell me or any of us that she loved us. But every time she asked us, 'have you eaten yet?' she gave us her heart, all the parts of it that never got hardened. She would have done the same for you, because she believed that there was nothing that pot on the stove couldn’t cure.

Christine has been gone a long time but she lives unmistakably on in my Aunt Chris, her namesake and the very best proof that there was indeed something special in that sauce. Aunt Chris has taken the warmest parts of her mother and brightened them, made them even more technicolor. Her heart is boundless and her love extends so much further than we could have imagined back in that tiny kitchen. She too is fearless, although she’d never think so. She too is brave, although she’d laugh if you suggest so. And she too has saved my life and many others, more than she’ll ever realize. If you ever meet her, you won’t want to leave her side, wherever you are. Though her eyes are deep brown, they still shine with something familiar, something softer. My grandmother would be so proud.

Today is my grandmother Christine’s birthday. Since moving to Italy I get asked quite a lot about my heritage: where I'm from, who my parents and grandparents are and were. It’s shorthand, knowing who someone is based on their family, although my foreignness makes that genealogical measuring stick mostly inapplicable. However, when I tell people that my grandmother's family came to the United States from Campania in the South and my grandfather's from Sicily, there is an instant recognition and understanding. Because my grandparents' heritage makes it logical that I should live here, that I should speak the language, that I should know how to gesticulate with my hands and communicate dissatisfaction, jubilance, ennui. At first I found this logic to be shaky, at best; after years of travelling in many different corners I have long since abandoned the notion that I should 'belong', strictly speaking, anywhere. But I wonder if perhaps there is something to it all. Because though I am not from here, I see faces that remind me of Christine DiGaetano. I see her constantly in people that I meet, especially fierce women with olive skin and sharp blue eyes who suffer no fools and smoke too much and refuse to be defeated. I see her in you, I see her in me, laughing in the far, precious, ever familiar corners of my mind.